Aims and Outputs

This lecture presents NATO’s role in providing security to Europe since the end of the Cold War. It examines the critical role NATO played in ensuring European security since the end of the Cold War and its adaptation to global geopolitical changes and challenges. NATO’s enlargement process since the end of the Cold War, its new partnership programs, and new cooperation mechanisms, as well as the new type of missions it engaged in, are discussed. It also deals with the emerging new roles NATO has assumed since the end of the Cold War and the current challenges it is facing in the Transatlantic area.

Sub-Headings

Introduction

Adapting to Post-Cold War Security Challenges

Expansion of NATO and Collective Defence

Crisis Management and Relations with the EU

Russian Challenge and the Renewed Focus on Defense

Conclusion

Introduction

The roots of (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) NATO can be traced back to the aftermath of World War II. The devastation caused by two world wars and the following geopolitical environment across Europe prompted the 12 founding members, including the United States, Canada, and several European countries, to seek collaborative solutions to prevent the emergence of future threats and provide collective security for themselves. It was established with the signing of the North Atlantic Treaty in Washington, D.C. on April 4, 1949. Its primary objective was to create a mutual defense pact, wherein an attack on one member would be considered an attack on all (article 5).

Since its inception in 1949, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) has played a crucial role in safeguarding European security. Born out of the need to counter the Soviet threat during the Cold War, it became the linchpin of the Western bloc’s security against the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact across the Transatlantic area. It played a crucial role in deterring aggression and ensuring security in Europe. The principle of collective defense, enshrined in Article 5 of the NATO treaty, proved essential in maintaining stability, as it acted as a deterrent against any potential aggressor.

NATO’s significance did not diminish with the fall of the Iron Curtain. Instead, it adapted and evolved to address new challenges in the post-Cold War era in the wider Transatlantic region and increasingly beyond.

Video: Winston Churchill’s Iron Curtain Speech, 5 March 1946, Fulton, Missouri, US

Source: https://winstonchurchill.org/resources/speeches/1946-1963-elder-statesman/the-sinews-of-peace/

This essay examines the critical role of NATO in ensuring European security since the end of the Cold War, its adaptation to global geopolitical changes, and the challenges it faces, focusing on its contributions to stability, cooperation, and collective defense in Europe and its neighborhood.

Adapting to Post-Cold War Security Challenges

The global landscape underwent significant transformations since the end of the Cold War, and NATO faced the challenge of adapting to new security paradigms and ensuring the stability of Europe and its surrounding regions during political upheavals and the emergence of new threats. Under the changing circumstances, NATO embraced “enlargement” to foster democratic principles, economic development, and security cooperation among European nations. The integration of former Eastern Bloc countries into NATO helped to solidify the continent’s security architecture and extend the “zone of peace”.

The post-Cold War era has brought new security challenges, including terrorism, cyber threats, and hybrid warfare, and NATO has responded to these by expanding its focus beyond the traditional military domain to encompass a broader range of security issues. In this aspect, NATO has increasingly invested over the years in cybersecurity, counterterrorism, and crisis management capabilities to effectively address these challenges. The creation of the NATO Response Force (NRF) and the enhanced focus on cyber defense and intelligence-sharing exemplify the alliance’s efforts to tackle new security challenges. NATO’s adaptability and commitment to addressing 21st-century threats have reinforced its relevance in European security affairs.

As part of its transformation and adaptation, the alliance has initially reduced the level of forces deployed (including a substantial reduction in nuclear forces), streamlined its integrated command structure, created new structures (such as the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council, replacing North Atlantic Cooperation Council) where non-member states could consult with NATO on security matters, and devised partnership programs (such as Partnership for Peace Program, Mediterranean Dialogue, and İstanbul Cooperation Initiative), so that partner countries work with NATO to develop their armed forces and cooperate with it in operations.

The multiplicity of various partnership programs indicates the recognition by NATO of the need for a comprehensive approach to security challenges. In this way, NATO has been able to cooperate on diverse security issues with non-member states and international organizations, not only in and around Europe but globally. These partnerships foster cooperation, share expertise, and contribute to global security. Especially the Partnership for Peace (PfP) program, launched in 1994, has been instrumental in building relationships with countries from Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, enhancing their capacity for defense and cooperation.

Furthermore, NATO has also engaged with other international organizations, such as the United Nations and the European Union, to address security challenges effectively. The alliance’s cooperation with the EU especially on issues like counterterrorism, cyber defense, and crisis management has helped to create a more integrated and coherent security framework in Europe.

Expansion of NATO and Collective Defence

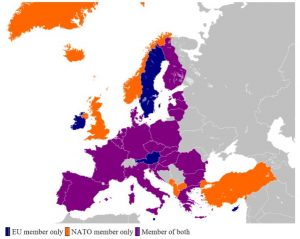

The end of the Cold War brought about a significant shift in NATO’s role. While it was exclusively engaged in deterrence and defense during the Cold War in the Transatlantic area, its newly assumed responsibilities expanded NATO’s areas of operation. However, the “collective defense” agenda and providing security to Europe remained as main priorities of the Alliance. One of the ways the Alliance extended security to the whole of Europe since the end of the Cold War was the enlargement of its coverage and membership.

In this regard, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the dissolution of the Eastern Bloc provided an opportunity for NATO to expand its membership. Starting with the inclusion of former Warsaw Pact countries such as Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic in 1999, NATO has continued to welcome new members. Its latest member is Finland, which became a NATO member on April 4, 2023, leaving its long-held neutrality due to threats it perceived because of Russian aggression against Ukraine since February 2022. These expansions offered stability and security, enjoyed long in Western Europe, to the East, Southeast, and now Northern Europe by integrating new members and providing reassurance to them by offering its security umbrella under NATO’s Treaty’s collective defense clause (Article 5).

Map 1: NATO Enlargement

Source: https://tr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dosya:History_of_NATO_enlargement.svg

NATO has demonstrated its commitment to collective defense since the end of the Cold War through various means. For example, its recent deployment of forces in Eastern Europe in response to Russia’s aggressive actions in Ukraine since 2014 reinforces the alliance’s commitment to deterring potential adversaries and defending its allies.

Crisis Management and Relations with the EU

In addition to collective defense, NATO has taken on an increasingly prominent role in crisis management and peacekeeping efforts. NATO’s involvement in the Balkans since the 1990s, through peacekeeping missions in Bosnia and Herzegovina and later in Kosovo, demonstrated the alliance’s capability and willingness to address regional conflicts and contribute to stability and peace.

Beyond its traditional role as a defense alliance, NATO has also engaged in humanitarian interventions to address crises beyond its borders. For instance, during the Kosovo conflict in the late 1990s, NATO launched an air campaign to halt the ethnic cleansing perpetrated by Serbian forces. The campaign demonstrated NATO’s willingness to intervene to protect human rights and regional stability. Similarly, its intervention in Libya in 2011 showed NATO’s willingness to intervene when necessary to protect civilians and uphold international law. However, such operations have also sparked debates about the organization’s mandate and the use of military force for humanitarian purposes.

Crisis management operations were also the driver of the debate on EU-NATO relations in the 1990s. While the EU member states argued for opening up a space for Europe (i.e., European Security and Defence Identity, ESDI) within NATO and making use of the assets and capabilities of the Alliance for EU operations, non-EU NATO countries, emphasizing the primacy of NATO for European security, were reluctant to duplication of efforts. In the end, a workable modus operandi emerged with the so-called Berlin Plus arrangements in 2002, whereby the EU was allowed to use the NATO operational planning and conduct capabilities on a case-by-case basis for operations the NATO was not going to involve. Currently, the only EU operation that makes use of NATO assets is Operation Althea which replaced NATO’s Stabilization Force (SFOR) in Bosnia & Herzegovina in December 2004 under the Berlin Plus arrangements.

Map 2: NATO and EU Membership

Source: Wikipedia Commons, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berlin_Plus_agreement#/media/File:EU_and_NATO.svg

Later on, the EU-NATO strategic partnership was enlarged with the Joint Declaration in July 2016, updated in July 2018, which outlined seven concrete areas where cooperation between the two organizations should be enhanced: 1) countering hybrid threats; 2) operational cooperation including sea and on migration; 3) cyber security and defense; 4) defense capabilities; 5) defense industry and research; 6) exercises; 7) supporting Eastern and Southern partners’ capacity-building efforts.

Russian Challenge and the Renewed Focus on Defense

Recent years have seen a resurgence of tensions between NATO and Russia. Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and its further military interventions in Ukraine have raised concerns about European security. In response, NATO has bolstered its presence in Eastern Europe, enhancing its deterrence capabilities and demonstrating its commitment to collective defense. However, these actions have also contributed to increased tensions between NATO and Russia.

Russian challenge is also dominating the current EU-NATO cooperation agenda. This unprecedented European security crisis has resulted in enhanced coordination between the EU and NATO as both organizations have taken measures in their areas of responsibility in a concerted effort to respond to Russia’s aggression and support Ukraine. Among others, the EU launched various sanctions against Russia, is reducing its energy dependency on Russian gas and oil, granted Ukraine EU candidate status, initiated new funds for the common procurement of military equipment to compensate for deliveries of weapon systems to Ukraine, is training Ukraine’s military personnel in Germany and Poland, and has been procuring artillery and rocket munitions for Ukraine. NATO, on the other hand, has increased its enhanced Forward Presence (eFP) in the three Baltic States and Eastern and Central Europe, has taken measures to enhance the protection of Allied airspace, welcomed Finland into the Alliance (to be followed by Sweden), strengthened the Comprehensive Assistance Package, providing Ukraine with all kinds of support, and continues to provide assistance and advice to Ukraine in countering hybrid threats and increasing resilience.

The war in Ukraine has made it clear and visible that only NATO can deter Russia and defend Europe if needed. Yet, the military force is not always the most suitable answer to new hybrid threats such as disinformation, election interference, cyberattacks, and exploiting economic vulnerabilities. Since the response to these types of threats requires a much wider societal approach, the EU, with its wide set of expertise and responsibilities in soft power areas, could play a larger role than NATO in countering these kinds of threats.

Conclusion

Since the end of the Cold War, NATO has played a vital role in maintaining European security and stability. Through the expansion of its membership, collective defense, crisis management, peacekeeping efforts, partnerships, and adaptation to new threats, NATO has remained a cornerstone of security in Europe. As the international security landscape continues to evolve, NATO’s ability to adapt and foster cooperation will be crucial in ensuring the continued peace and prosperity of the European continent.

From its origins during the Cold War to its adaptation in the post-Cold War era, NATO has demonstrated its resilience in maintaining peace and stability. The alliance has evolved to address contemporary challenges, expanding its focus beyond traditional military defense to encompass broader security issues. As the world continues to change, NATO continues to adapt, foster cooperation among its members, and reaffirm its commitment to collective defense, upholding its crucial role in securing Europe.

Further Reading

Borrell, Joseph. 2020. “EU-NATO cooperation”, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/eu_nato_factshee_november-2020-v2.pdf

Graeger, Nina. 2016. “European security as practice: EU–NATO communities of practice in the making?” European Security, 25 (4): 478-501.

Haglund, David G. 2003. “Community of Fate or Marriage of Convenience? ESDP and the Future of Transatlantic Identity”. In: A. Moens, L. J. Cohen & A. G. Sens (eds.), NATO and European Security: Alliance Politics from the End of the Cold War to the Age of Terrorism: Alliance Politics from the End of the Cold War to the Age of Terrorism. ABC-CLIO: 32-49.

Howorth, Jolyon. 2018. “Strategic autonomy and EU-NATO cooperation: threat or opportunity for transatlantic defence relations?” Journal of European Integration, 40 (5): 523-537.

Piechowicz, Michal and Justyna Maliszewska-Nienartowicz. 2020. “EU-NATO relations through the lens of strategic documents.” Romanian Journal of European Affairs 20 (2): 18-35.

Petrov, Petar and Iulian Romanshyn. 2020. “Capability development in Europe: how can the EU defense push benefit the transatlantic partnership?” Atlantisch Perspectief, 44 (3): 54-58.

Spassov, Philip. 2014. “NATO, Russia and European Security: Lessons Learned from Conflicts in Kosovo and Libya”. Connections, 13 (3): 21-40.

Volten, Peter M. E. 2014. “Transatlantic Security, Defence and Strategy: Badly Needed Reforms”. Europolity, 8 (2): 7-18.

Audio-Visual Recommendation

CISAC Stanford podcast series, “European Defense and Security: EU-NATO and Transatlantic Dynamics”, 3 May 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rOmLa_XcaJc&list=PLz31jYTN4xtmIE4etfkBxFbEHjyqiGADT&index=19&t=1s.

Into Europe podcast series, “How Europe and the USA’s relationship is changing”, 25 September 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4A–jv2oTWs&list=PLz31jYTN4xtmIE4etfkBxFbEHjyqiGADT&index=21.

VisualPolitik Podcast series, “Europe’s REARMING to defend itself against RUSSIA: A new era for the EU?”, 20 March 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Rnj–DIghc&list=PLz31jYTN4xtmIE4etfkBxFbEHjyqiGADT&index=22.

Atlantic Council, “Charles Fries; Orienting European security: The EU Strategic Compass and EU-US defense cooperation”, 4 April 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xcCMixuTQ6o&t=22s.

Hudson Institute, “Poland, NATO, and the Future of Eastern European Security, 27 June 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dckWnhSO-EA.

Bologna Institute for Policy Research, SeminarCast podcast episode on “European Security between NATO and the EU”, October 2014, https://open.spotify.com/episode/5bHRT6knUNYMRpjb8W0YwB?si=c2a992622f9f4ddd.

Utrikespodden med Axel och Zebulon podcast series, “Latvia’s former Defence Minister on Ukraine and European Security”, March 2022, https://open.spotify.com/episode/1F2jibUXkxtwNftK4bGv2O?si=4382aaa273b94285.